The year of 1917 was one of great change for the Russians. The Great War had taken them all. And all they wanted was the withdrawal of Russia from the front. That, and democracy. These things were promised by Aleksandr Kerensky and by his provisional government.

In his youth, Kerensky wished to become an artist. But gradually, spending most of his time among the intellectuals of St. Petersburg, he realized he could not serve his homeland by culture alone. His dislike of the monarchy and the royal family turned into hatred – and, in order to do something for Russia, he had to act. The first step was to abandon the subjects he loved and to study law. He graduated in 1904 and got married the same year with Olga Lvovna Baranovskaia, the daughter of a Russian general. At the same time, Kerensky made the decision to join the ever-growing ranks of rebellious Russians, thus putting his knowledge in the service of the simple man: he had become one of the revolutionary socialists, the heirs of the Narodnaia organization – the “People’s Will”. The “Bloody Sunday” of 1905 caught him on the crowded Nevski Prospekt street where the slaughter took place. It was there when Kerensky realized that something great was about to happen and became convinced that there was no peace to be had between the people and the tsar.

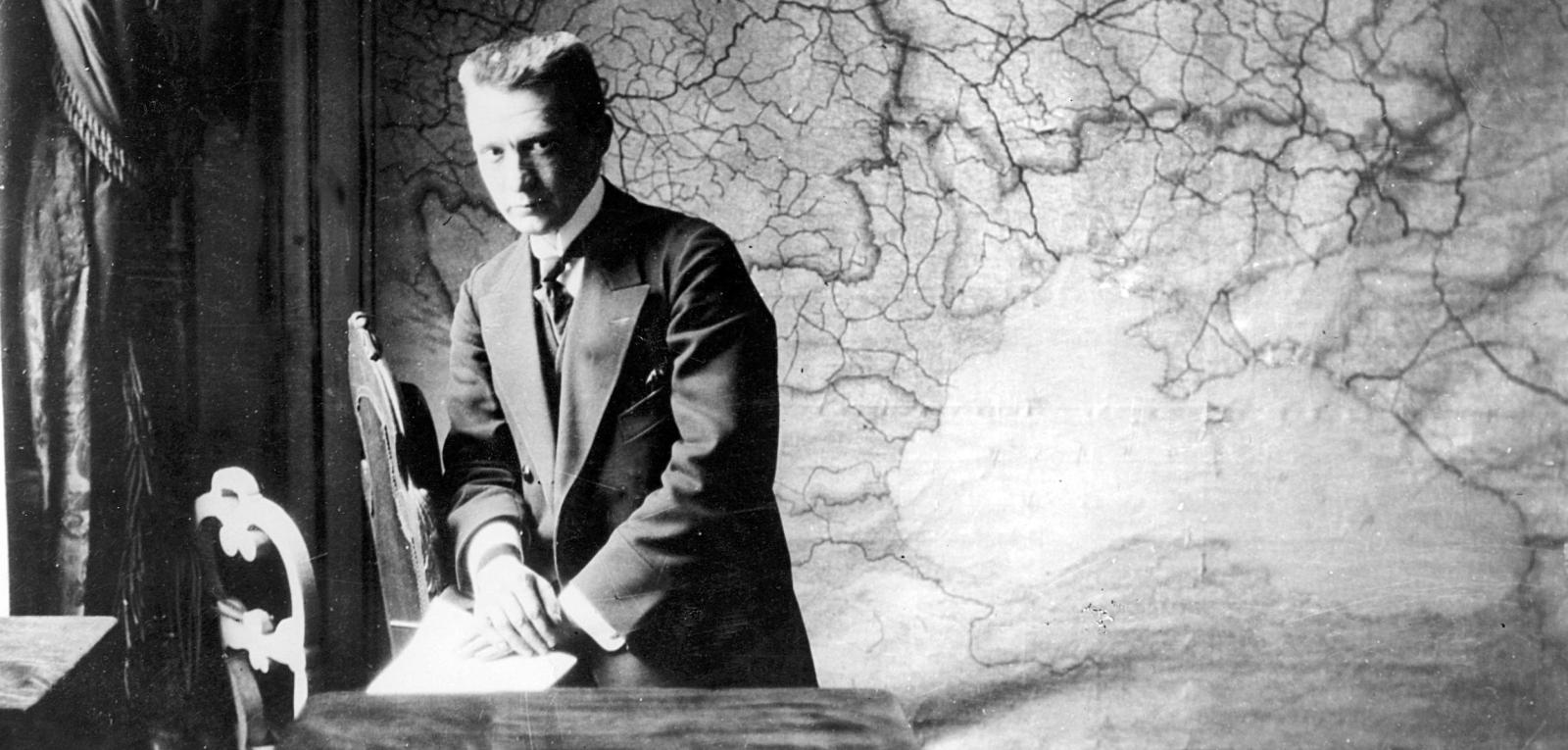

At 25, Aleksandr Kerensky made his debut as a lawyer, and his passion and talent as an orator, but above all the desire to unmask the injustices of the Tsarist regime, had quickly brought him success. He made a name for himself in the Armenian Revolutionary Federation trial where, out of the 146 accused, he managed to acquit 95. Kerensky seemed to be the perfect man that the State Dume members wanted to present to the people – he was objective, skeptical and good with the words. So, in 1912 he was appointed to represent the Labor Party, or trudovikii, as they were also called, within the legislature. Subsequently, in the preparation of the first Provisional Government, in March 1917, the office of the Minister of Justice was made available. Ciheidze had refused to take it, and Kerensky knew that this was his chance. So, he went in front of the Soviet assembly and, in a well-orchestrated scene, he asked for their permission to be a member of the government.

The Provisional Government, which had as its Prime Minister prince Lvov, was bringing democracy to Russia. And the main subject on the agenda was war. The Soviet was clear: national unity of Russia, aimed at a democratic peace, without imperialist claims or reparations. The Provisional Government issued a “Declaration of War Stakes” which, in general, went on the same idea of peace promoted by the Soviet. But at the end, Foreign Minister Miliukov added as a personal note that Russia still needs a “decisive victory.” This has led to a number of major changes. Lvov proposed to Zereteli, an authoritarian Menshevik, that Soviets should join the government, with the promise that Miliukov would be forced to leave. The moves were made, and with Gucikov’s resignation, Kerensky now occupied the post of war minister. He accepted it with joy, believing that the main objective of the Provisional Government was to defend the country.

At the beginning of May 1917, Kerensky’s first decision as war minister was the appointment of Brusilov as supreme commander of the army. And the first ruling on the war was the initiation of an offensive against the Germans and Austrians. It was the wrong decision – on one side Brusilov had already warned him about it and on the other hand soldiers deserted or refused to leave on the front. In just three days, the attack turned into a retreat. The soldiers simply did not want to fight. In the eyes of the people, the Provisional Government had failed both on a military and on a diplomatic level. In Russian politics there was chaos, and Prince Lvov appointed Kerensky as prime minister.

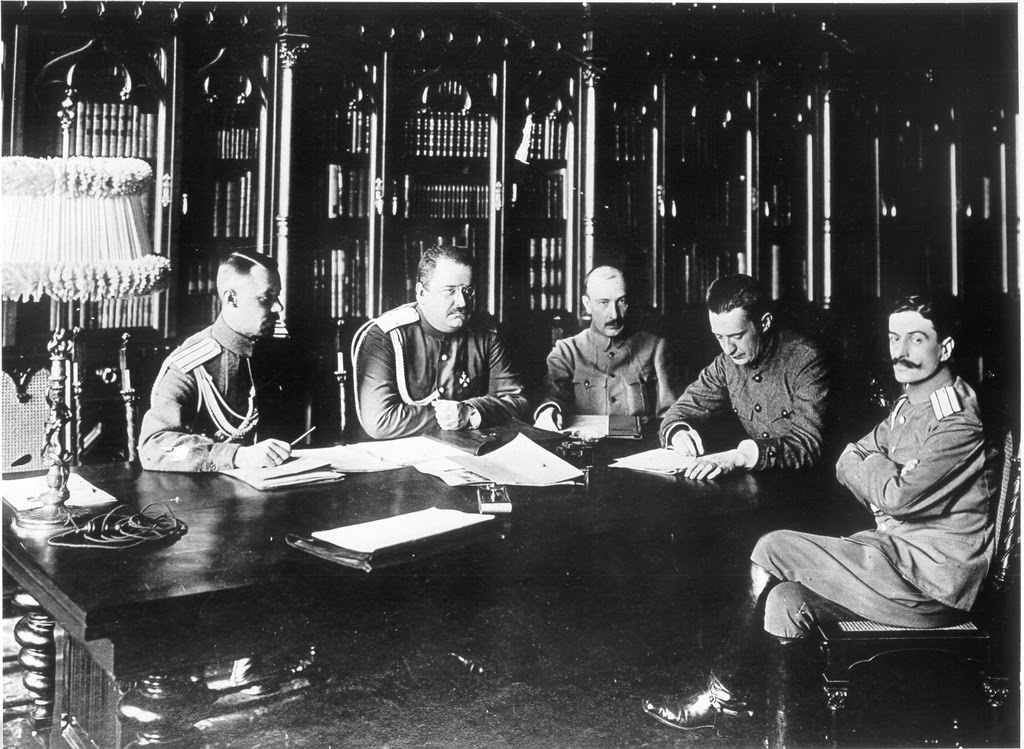

After the military failure in June, it was clear that Brusilov was no longer wanted as commander of the army. The one who replaced him was General Lavr Kornilov, a man who most of all upheld military tradition. Kornilov had his own program he wanted to impose. For example, shortly after he was appointed supreme commander of the army, he demanded the reinstatement of the death penalty for deserters. But Kornilov’s plans were far-reaching: he was planning a coup. Kornilov showed his true colours on the 10th of August 1917, when he appeared at the Winter Palace with his bodyguard, armed with two machine guns. He then threatened that his reforms would be accepted either voluntarily or through violence. Seeing that the situation is out of control, that the country’s chaos is increasing and that he has gradually abandoned the idea of the two united political worlds, Kerensky organized a national conference in Moscow.

After several meetings, Kerensky asked Kornilov to tell him the terms of his ultimatum. There were three, and it was tough: the imposition of the martial law in Petrograd, the transfer of all civilian authority to the supreme commander and the resignation of all ministers, including Kerensky. It essentially was a military coup. But Kerensky had foreseen it. He accused Kornilov of treason, and his own soldiers deserted him: he was placed under house arrest and then transferred to a monastery in Bijov. As for Kerensky, although apparently the “Kornilov Affair”, as the event was called, had ended well, it had caused great damage to his image. In just two months, in September 1917, Kerensky headed a five-member directorate. The last remarkable decision he took from the position of prime minister was to proclaim Russia as a republic on the 15th of September. Kerensky tried to teach the Russians some of the principles of democracy, but it seems to have been too much. On the night of November 6 to November 7, the Bolsheviks took power, and Kerensky fled to France.