Between July 28, 1917 and August 27, 1916, Romania maintained its neutrality as the First World War raged on. The geostrategic position in which the country found itself and the resources available at its disposal prompted both the Entente and the Central Powers to undertake considerable efforts to attract Romania into the conflagration. Nevertheless, both Romanian society and the vast majority of political leaders were close to the Entente.

When the First World War started, Romania was a member of the Triple Alliance ever since 1883. Starting with 1907, Bucharest began to distance itself, slowly but surely, from the alliance with Austria-Hungary. Romania’s position regarding the conflict was discussed in the Crown Council convened on August 3, 1914 by King Carol I of Romania. He declared himself against neutrality and wanted to enter the war on the side of the Central Powers and argued his point on the basis of the provisions to which Romania agreed in order to join the Triple Alliance.

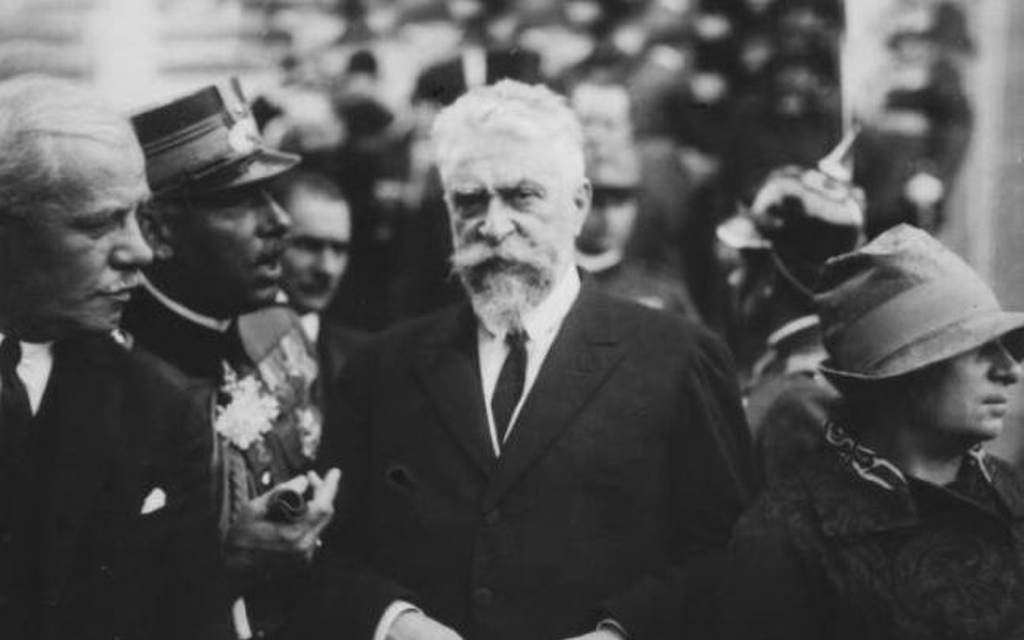

Ion I. C. Brătianu takes over the political reins

On the other hand, Prime Minister Ion I. C. Brătianu and the vast majority of those who participated in the Council supported the neutrality of the country. The main argument was that the Treaty of 1883 required Romania’s entry into war, only if the Central Powers were attacked. In this case, Germany and Austria-Hungary were the ones attacking Serbia, When Italy, which had signed with the Central Powers a similar treaty to that of Romania took the decision to remain neutral, the die was cast. Romania decided to remain neutral. King Carol I accepted the Council’s decision, though he was strongly affected by the fact that Romania would not enter the war. Ill and upset by the turn of the events, he would die on October 10, 1914. His 49-year-old nephew, Ferdinand, would become the new King of Romania.

However, the real political power will be concentrated in the hands of Prime Minister Ion I. C. Brătianu, one of Romania’s most complex personalities. Reserved, distant and sober, Brătianu was adored by his collaborators and vehemently attacked by his adversaries. He took decisions exasperatingly slow. He examined them, re-examined them, and thought them over even more carefully. He will be the one to negotiate directly with representatives of the Great Powers in Bucharest, sometimes even bypassing the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of his own cabinet. He will quickly secure the support of King Ferdinand and Queen Marie, and from the end of 1914, he began a process of preparing the country for war. He was aware that Romania was in a vulnerable strategic position and was not going to go to war until there was a reasonable chance of winning it.

Brătianu was to prove himself a master of diplomatic play and navigated with great skill between the Entente and the Central Powers. Thus, on September 23, 1914, Romania concluded a neutrality agreement with Italy. A few days later, on October 1, the authorities in Bucharest signed an agreement with the Russian Empire. The agreement stipulated that, in exchange for Romania’s benevolent neutrality, Russia would recognize its right over the Austro-Hungarian provinces inhabited by Romanians and agreed to let the country choose on its own accord the moment when it will occupy them.

The agreement basically revealed Romania’s objectives and the direction in which it was heading. Even so, Russia did not offer any guarantee that Romania would acquire these territories, and the United Kingdom and France were not a part of the deal. They finally joined Russia at the bargaining table at the beginning of 1915, but they considered that Brătianu’s territorial claims were exaggerated: Banat, Crişana, Maramureş, Bukovina and Transylvania.

The Entente is changing its tune

The attitude of Great Britain and France changed in the summer of 1915 after new developments on the frontlines. The enormous losses of those months on the Allied West Front and the defeat of the Russians in Poland convinced the Entente that Romania’s intervention in their conflict is a necessity. There was now a considerable pressure on Romania to enter into the conflict.

In July, the Entente accepted Romania’s wishes with the condition to enter the war within five weeks. This time, the one who refused this pact was Brătianu, who stated that the Romanian entry into the war at that moment, when the Central Powers had the upper hand, would be a suicide for the country. Even so, the negotiations with the Entente were too far along. What remained was only to choose when Romania would enter the war.

It is worth mentioning that the Entente was the first to promise Transylvania to Romania, but not the only one.

Earlier that summer, as the signs, rumours, and special information was gathering- in the sense of Romania’s entry into war on the side of the Entente- Berlin suggested to Bucharest (June 1916) that, in return for maintaining its neutrality (at least) it might reconsider Romanian claims on Transylvania. But it was too late.

In the summer of 1916, the military situation was again in favour of the Entente. The German army failed to conquer Verdun, the Allies were gathering an army in Thessaloniki, the British were preparing a big offensive on the Somme, and the Russians were launching their last successful big offensive, that of General Aleksei Brusilov. It seemed that this was the moment expected by Brătianu.

On the other hand, even if the military situation appeared to be favourable to the Entente, the geostrategic situation of Romania had changed negatively by the entry into the war of Bulgaria (October 1915) on the side of the Central Powers. Thus, Romania had another enemy in the south and the only border and secure connection with the Entente was to the east of the country, with the Russian Empire.

The Central Powers were also not prepared to give up on Romania. In addition to powerful propaganda, they exerted diplomatic pressure, and they made it clear that they would use military action to prevent Romania from joining the Entente, but also to buy the grain and oil they desperately needed.

Nevertheless, on July 4, 1916, Brătianu announces the Entente that Romania is ready to join the alliance. Negotiations will last for five more weeks delaying the entry into the war until August 27.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa

Selective bibliography:

Glenn E. Torrey, România în Primul Război Mondial [Romania in the First World War], Meteor Publishing, Bucharest, 2014.

I.G. Duca, Memorii [Memories], vol. I, Expres Publishing House, Bucharest, 1992.

Henri Prost, Destinul României: (1918-1954) [The destiny of Romania: (1918-1954)], Compania Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.

Paul Cernovodeanu, Basarabia: drama unei provincii istorice româneşti în context politic internaţional: (1806-1920) [Bessarabia: the drama of a Romanian historical province in an international political context: (1806-1920)], Albatros Publishing House, Bucharest, 1993.

Nicolae Ciachir, Basarabia sub stăpânire ţaristă: (1812-1917) [Bessarabia under tsarist rule: (1812-1917)], Didactic and Pedagogical Publishing House, Bucharest, 1992